I was doing some cleaning out of the computer files and found some old item. This is a letter I wrote back in 2009 to the Lochac Order of the Laurel (the SCA’s award for top level arts and crafts practitioners). At the time I was the only dedicated armourer in that group and they were trying to determine what the standards should be. Being a bit focused on providing some objective criteria, I attempted to get my ideas written down.

I give you here the first part, which is the general standards. I wrote a full rundown of what various other people were doing and what their skills and abilities were. That bit will remain unpublished.

Some notes about standards and assumptions for the laurel.

Ok this might be a bit long but bear with me. I think I need to get some of my thoughts and assumptions expressed for general comment and consideration. It is better that we look at what the order is looking for as far as standards go before we apply that to particular candidates.

Sorry if I drop too far into jargon – I can answer any technical question if anyone wants me to.

What are we looking for in a laurel level armourer?

Think of this as costume as it makes a good comparison (but this does have its limits).

The art of armouring has advanced massively in the past few years. Some of this advance is due to the internet with the ability to share information and resources but also with the publication of Techniques of Medieval Armour Reproduction (TOMAR).

TOMAR

It can be said that there is now a ‘TOMAR standard’ The TOMAR standard has in effect raised the bar on what we can expect from people working in the armour field. If someone is capable of executing the projects in TOMAR then we would recognise them as being a reasonable journeyman standard, about were a Kingdom level award would sit. The TOMAR projects walk you though all the major bits of harness and is mostly 14thC transitional gear with basic embellishments.

Before TOMAR, we had to make a lot up by trial and error and experimentation. Now the basic skills and techniques are clearly set out and explained. When I was admitted to the order, techniques like raising were considered only for the very advanced, but have now become part of the basic skill set.

The general body of armouring skills and knowledge has progressed significantly.

So the skill set I would be looking for in peerage level armour would be:

Common use of appropriate techniques.

Sinking, ridging planishing and fluting form the backbone of working techniques.

Raising should be well understood and be used.

I would expect the candidate to be using cut and weld only were appropriate (this will be a bit of a discussion topic).

I would expect the person to be able to use these techniques with reasonable speed and accuracy.

A well developed understanding and application of heat processes (annealing, hot work, shrinking and tempering).

Ability to capture the right shapes and line of the original forms.

This can be really hard to define. The example would be like some of the costuming. One outfit may look fine to a casual observer but to someone who knows what to look for, the seams are in the wrong place, the waist is too low, etc.

Attention to using the appropriate materials is important.

Many period pieces display a subtlety of line and shape that can be hard to pick unless to are looking for it, but contribute to the overall look.

Work needs to look like a period example on close examination?

Finishing

They must finish the pieces to the appropriate level. This does not mean how high can you get the polish. I would be looking at the cleanliness of the ridges flutes and rolls, the accuracy of the general hammer work and the crispness of the planishing and sanding.

The edges need to be finished – there are several different common edge treatments from the period.

They should be making the catches, hinges and other add-ons.

Should be able to make buckles (and plates) and does so.

Strapping and leather work should be of high standard

Should be able to produce historically correct liners and suspension.

Functionality

All the pieces should work well together and function to both protect the wearer and allow appropriate range of movement.

The candidate needs to have an excellent understanding of fitting and attaching the components of harness.

Does it all work?

I do not expect the person to be able to create the foundation garments, but they do need an understanding on how they affect/support the harness.

Research

The candidate has a very good understanding of the historical record.

The candidate is able to reproduce a given primary example or be able to work in the style of a given school/centre.

The person understands the differences between the dominant styles and forms.

As a side note we no longer recommend laurels in ‘costuming’ we recommend them for making, understanding and being able to explain the clothes and accessories for one or more particular times and places. So are we looking for an area/component of specialisation?

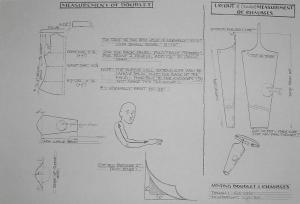

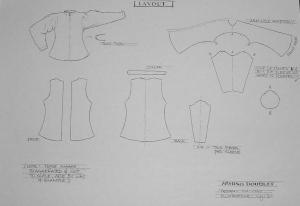

Patterning

The candidate can draft their own patterns and understand how to alter templates to achieve various form changes.

Body of work

I would look at the consumers for a guide on this. There will need to be a reasonable body of pieces out there at an appropriate level. I would suggest that we would not consider many of the SCA sport armours (mostly cut and weld constructions, made to meet a price point) as being ‘at level’. We would not think about giving a Laurel to a costumer who made lots of basic T-tunics…

Advancing the Art

The candidate must be bringing something new to the field or excelling and pushing the levels in well-trodden ground.

Effect on the Kingdom

I would be looking at the candidate’s effect on their own group and the Kingdom as a whole. They should be encouraging the adoption of more period harness and field presentation?

Teaching and promoting the arts also come in here.

I will not go into the general Peerage criteria, as it is part of a more generalist conversation that everyone can join in on.